EXTENDED THROUGH SEPTEMBER

TIBET HOUSE NYC

VISIONS OF ENLIGHTENMENT:

MONUMENTAL PHOTOGRAPHS BY:

PETER VAN HAM

At an altitude of ten thousand feet nestled in a lush valley surrounded by the majestic Himalayas, the world-renowned Buddhist monastery complex of Alchi is a destination for art lovers and seekers alike. Mandalas and towering sculptures of Bodhisattvas adorn the walls, ceilings and doors of each temple and include scenes from the Buddha’s life as well as secular life from a period of tremendous cross-cultural activity in the region. Alchi holds some of the oldest surviving paintings in Ladakh:

“… Mesmerizing colored patterns scroll across the wood beams overhead; the temple’s walls are covered with hundreds of small seated Buddhas, finely painted in ocher, black, green, azurite and gold.”

– Jeremy Kahn, Smithsonian

TIBET HOUSE US GALLERY -NYC

EXTENDED THROUGH SEPTEMBER

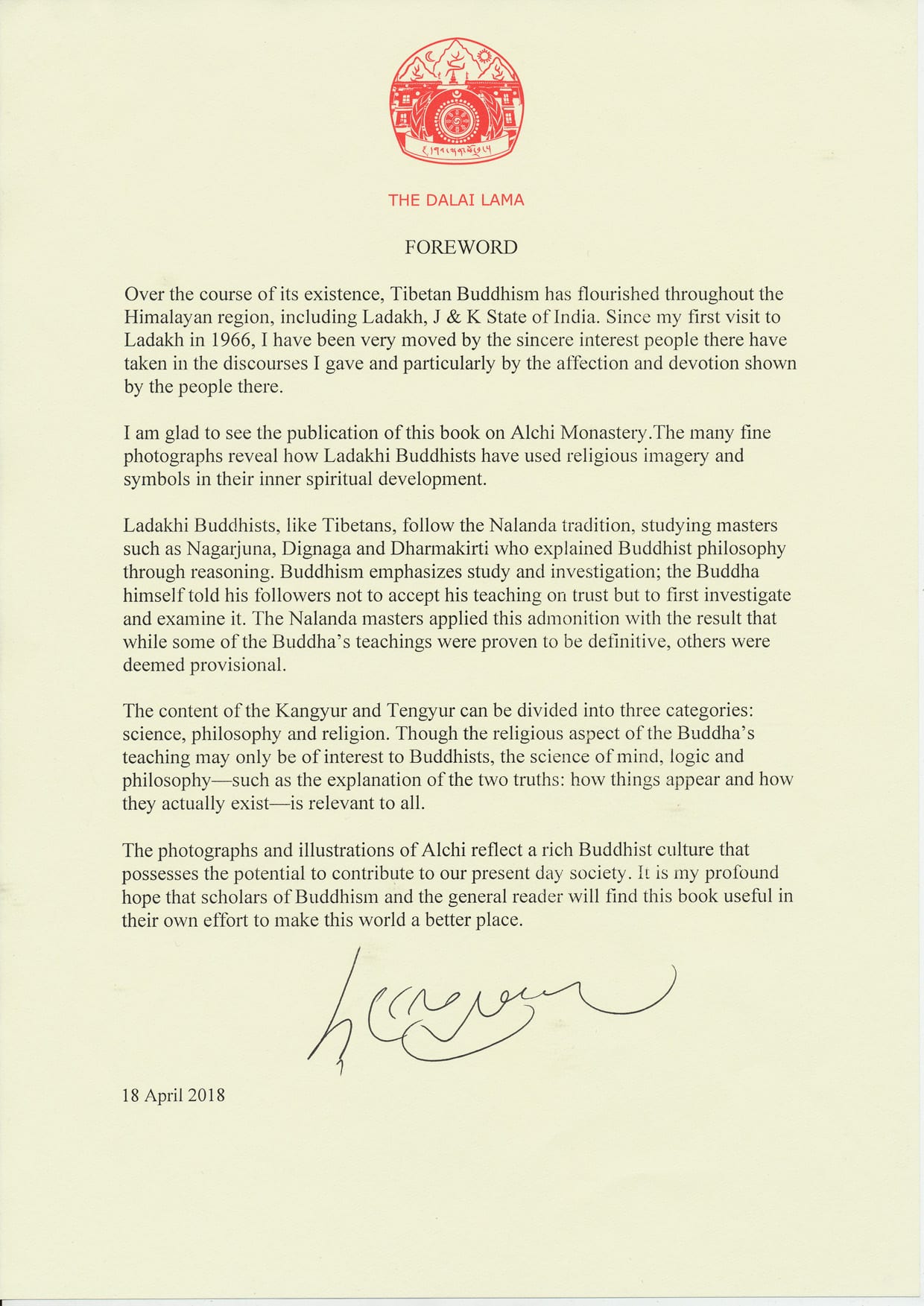

- LETTER FROM HH THE DALAI LAMA

- INTRODUCTION

- history

- The Monastic Compound

- SPIRITUAL CONCEPTS

- The Art of Alchi

- Photographer / Author/ Curator Peter van Ham

- purchase Exhibition Catalog

- SPONSORS

From southwest to northeast the temples are:

New Temple – Lhakhang Soma

Three-tiered Temple – Sumtsek

Congregation Hall – Dukhang

Translator’s Temple – Lotsava Lhakhang

Manjushri Temple – Jampal Lhakhang

Originally, the Dukhang was the center of the compound with the stupas leading towards it. The construction technique of all the temple buildings at Alchi follows Tibetan modes. The 0.75 cm to nearly one meter-thick walls consist of natural rocks and loam to which is added external plastering of layers of clay whitewashed with lime. Willow branches are used for the flat, plastered and brown-painted roofs. Structurally, these typical Tibetan buildings are enriched by horizontal bands, placed along the margins of the roofs and painted brown-reddish, as well as woodwork added to the façades that is clearly not of Tibetan/Ladakhi but rather South Central Asian in origin, and has possibly been carved by craftsmen from greater Kashmir. These intricately carved wooden elements such as doorframes, pillars, columns, capitals, and trefoliated arches are especially prominent at the Dukhang, the Sumtsek, and the Jampal Lhakhang. They feature curious similarities to stylistic traits found in temple architecture of Ancient Greece.

“Vairochana” means “light” and is conceived as the personified Dharma (Buddhist doctrine standing for “truth”), having the power to create, like light, encompassing all things, like space, and pervading all things, like the vital forces (energy) of the universe. Vairochana symbolizes the indiscriminate primeval consciousness from which the cosmos is understood to emanate in three, later five, main categories. The preference for cults focusing on Vairochana, which were thus found as depictions on the walls of the kingdom’s religious foundations, is derived from the fact that those were the favored cults of the first ruling elite of Central Tibet, the Purgyul dynasty, in the eighth century, from which stemmed the rulers of West Tibet. An association with the cults worshipped by them as the first Buddhist rulers of a unified Tibet signified a direct continuation of their legacy. Their respective manifold liturgical cycles had all been translated into Tibetan during the second half of the eighth century.

Mandalas focusing on Vairochana in various forms are found as the dominant theme of the Dukhang and the second floor of the Sumtsek, where the monks were initiated into the esoteric teachings serving cosmic realization / access to the realm of pure forms (Sambhogakaya). The interior of this three-tier temple has been conceptualized according to an overall iconographic program that incorporates the interior design of all three floors of the building. Its architecture is based on a mandala-type diagram made of a concentric, interrelating system of squares that were then transformed into a horizontal arrangement of spaces. The vertical conception is borne from the idea of a spiritual ascent from lower to higher planes which, again, is mirrored by the themes artistically represented on the walls of the temple’s different floors. From the ground up to the lantern ceiling, where only a few mandalas of special significance for the period when Alchi was founded are located and thus might be taken as representing the realm of formlessness (Dharmakaya), the devotee is confronted with increasingly purified manifestations of the exalted realm. Signified by three colossal Bodhisattva sculptures placed into the three niches at the west, south and north walls, the iconographic program of the first floor presents the adept with instruments for purifying body, speech and mind. As may be derived from the depictions that cover the wrap-around skirts (dhoti) of the three Bodhisattva sculptures, the realm represented by the first floor is that of the world of human existence, however, in idealized form, the images serving as examples of virtues possibly to be achieved in this, mundane, existence. Thus, they may be interpreted as means of motivation for the devotee – the Life of Buddha Shakyamuni on Maitreya’s dhoti as the salvific history per se, the Mahasiddhas on Manjushri’s dhoti as examples of unorthodox behavior as expressions of enlightened states of existence, and the depictions on Avalokiteshvara’s dhoti of honorific laypeople such as West Tibetan kings and noblemen that devote their lives to pious offering and worshipping. All these are means of achieving merit in this world and are expressions of the manifestation of Nirmanakaya, the presence of enlightenment in the physical world. Under the latter fall also the depictions of the Bodhisattvas on the walls of the temple as well as those of donors and patrons in the lower registers of the first floor’s wall accompanied by laudatory inscriptions. The principle present in all these depictions is that of the assembly. Large groups of devotees and attendants flank the central figures, listening to their teachings, worshipping them and extending ritual offerings to them. The impression transmitted is one of joyful representations of glorious celestial abodes that, through the pious acts of the donors, are materialized in the mundane world. Incorporating images of monks and donors into the assemblies of celestial beings might have served the idea that the spectator/devotee may also become a part of such an assembly, possibly by following their pious example.

Connected to the idea of putting purifying instruments at the disposal of the devotee are the depictions of guardian deities on the entrance walls of each floor. Next to their apotropaic functions and representing virtues essential to the fulfillment of the spiritual task, they remind the entering devotee that he is supposed to have developed basic ethics before turning to the process of cosmic realization. Experiences to be gained from the meditative process, finally, are represented by the depictions of the thousand-fold multiplication of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas painted on the walls between the three colossal sculptures.

Styles, Motifs and Traits Found in the Art of Alchi: Entering the Dukhang and especially the Sumtsek temple, one is struck by the sheer complexity of the walls’ decorations, which, at the Sumtsek, and presumably also originally at the Dukhang, includes also the ceiling(s). Not only is every single centimeter of wall space filled with paintings that, in many instances, bear the character of miniatures, but what has been depicted here is exceedingly rich in detail and extremely fine in execution. These sophisticated features are combined with a highly developed feeling of the executing artists for the effective use and distribution of brilliant colors as well as a consistently superior level of imagination and fantasy in transferring the iconographic prescriptions into painting. Technical skill, taste and finesse exhibited by the artists concern all aspects of the artistic presentation, be it the shading of a skin portion of a large figure or even miniature-like attendants, the variant and multicolored outlines of a cloth design and its combination of colors, the elegant twist of energy rays emanating a deity, the delicate line in which attributes held by small depictions of Bodhisattvas in mandalas are painted (seemingly executed with single-haired brushes), the abundant jewelry, or the decorative elements such as volutes, borders and floral structures. It is striking how much the artists seem to have been aware of the effect of their art in the sense that finesse and volume of the figural depictions – and with these the feeling of awe created in the spectator – increase when viewed from the appropriate distance. Abundance and finesse as the main aspects of the art of the early Alchi temples serve the communication of devotion and exaltation in regard of the subjects displayed. Interestingly, there is a difference in the degree of minute execution between the panels devoted to single deities such as Tara, Amitabha or Manjushri and the deities of mandalas whose execution is, generally speaking, slightly less detailed. However, this difference in minuteness is balanced by the rich detail and sumptuous design of the mandalas’ structures and embellishments as well as subsidiary figures such as gandharvas. Thus, for example, gilded pastiglia applications – white lead applied in low relief – used among the single deities to highlight crowns, jewelry, and sometimes even full dresses, are used in the mandalas to form the vajra-borders that demarcate the various mandala compartments.

Landscape in the paintings of Alchi is never realistic or actual but always ideal, representational and symbolic in character. Perspective is not existent and side view is often mixed with plan. Depictions of architectural structures, limited to the dhoti of the Avalokiteshvara sculpture in the Sumtsek, however, are realistic and may be traced back to Hindu temples of Northern India (Kashmir, Chamba, Kullu) as well as palace and temple structures of West Tibet (Tholing/Guge kingdom). Generally speaking, the representation of human figures in the Dukhang and the Sumtsek – iconic figures of the pantheon and secular figures – is executed in Kashmiri/West Tibetan style. This implies idealized human body depictions with exaggerated proportions. Typical is the male torso with a ripple of abdominal muscles and highly athletic broad shoulders, while the female torso has an hourglass shape with a tiny waist, accentuating the prominent curves of breasts and hips. The extremities are fairly long, slender and delicate in shape. Faces are rather broad with almond-shaped eyes, those of frontally depicted iconic deities slightly squinting in order to convey states of bliss, often delineated with a black (and/or red) outline. A typical stylistic trait is the extension of the eye normally averted from the beholder across the figure’s head’s outer edge, thus creating a three-quarter image of what is rather a sideways depiction. Noses are slim and lips often fairly compressed between rather chubby cheeks. Three semicircular lines on the necks enhance the chubby ideal. Hair is long and often stylized-curly at the strands and the hairline with a clear middle parting resulting in a pronounced triangle at the forehead, in one way or another. As a rule, deities are surrounded by two halos–one around the head and one around the entire figure, ranging from round to oval. Both, male and female Bodhisattvas are highly adorned with princely regalia: their crowns are divided into three to five triangular panels with crescents above rows of pearls, ornate rings hang from the elongated earlobes, sometimes a second pair of earrings adorns the upper cartilage, arm rings, bracelets, bangles and anklets embellish the extremities. Typical Kashmiri stylistic traits are pointed veils for female figures and lotus garlands (padma mala) for female as well as male deities. Often they are interchanged with garlands of pearls that, among standing figures, extend as far down as the ankles. These garlands are part of a multitude of scarfs and shawls worn by the figures that surround them in an aesthetically pleasing curvy and whirling yet controlled manner thus creating the illusion of lightness, airiness and a wind-caressed atmosphere of the composition.

The multitude of fabrics worn by both, iconic and secular figures is the true treasure house of the art of Alchi. In it is revealed the amazing, far-reaching, and cosmopolitan range of influences that had been maturely incorporated into and assimilated by West Tibetan/Kashmiri art when it was lavishly spread out in the early Alchi temples, nowhere stronger and richer than on the various floors of the Sumtsek temple. Influences to be detected are varied:

Mainland and Northwestern India (Gujarat, Punjab, Kashmir)

Iran with roots dating centuries back to the Sassanian culture (third to seventh century CE) and motifs that may even be traced to the preceding Parthian empire (from third century BCE to 224 CE)

Central Asia

Tibet

Greece (Gandhara)

It is this amalgamation of such great variety of impulses, the combination of Indian, Iranian and Central Asian traits and motifs and their transformation to an entirely new, formative and independent form of art that creates the unique significance of the art of Alchi. Reasons for the exceedingly rich use of this multicultural visual language, next to the demonstration of devotion to and veneration of concepts that had been accepted as ultimate paths leading to enlightenment, is the documentation of the status of the executive patrons – the kings of West Tibet and their vicegerents and ministers – and the visual representation of their still upheld claim to the regency over Central Tibet that used to encompass most of the areas they draw from for their artistic treasury of signs.

Supported by H.H. the Dalai Lama, the Archaeological Survey of India and UNESCO, Peter van Ham has shed new light on one of the most remote places of human heritage. He is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society and the Royal Geographical Societies, London, and a Fellow of the Explorers Club, New York. Since 2004, he has been chairing the charitable Society for the Preservation and Promotion of Asian Heritage (SPAH) supporting research, documentation, and presentation.

Alchi: Treasure of the Himalayas

Ladakh’s Buddhist Masterpiece

Peter van Ham with Amy Heller and Likir Monastery

Foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

422 pages, 600 illustrations in color

1 fold-out, maps, drawings, 29 x 31 cm, hardcover w/dustwrap

ISBN: 978-3-7774-3093-5

See David Shulman’s review of ALCHI in the New York Review of Books

https://www.nybooks.com/online/2018/12/05/the-ravishing-art-of-alchi/

Copies available onsite at Tibet House US

22 west 15th street

New York, NY 10011

We gratefully acknowledge sponsorship and support from the following organizations and individuals.